When it comes to the work around examination and investigation, there are many tasks that are fairly simple, repetitive, and still require more than 2 seconds of your time. Production of labels, documents, preparing storage media – for years we’ve had templates for the work that’s almost pro forma, but why are we still using our own time to make the same five, ten, twenty clicks over and over again? If the task itself does not require DF or even human expertise, a human does not need to do it.

Even more important, is what I call the problem of “dead time” – time when either a person cannot work because their station is busy, or a station is waiting for human input. I don’t work 24 hours a day, so there is of course time when my computer needs me to click a button and I’m tucked up nicely in bed or 4 episodes deep into a binge. Automation can prevent cases where processing is delayed for a weekend because software needed some boxes ticked and buttons clicked.

The Current State

Case Management Systems can help with documents – it’s thankfully been a long time since I’ve had to manually complete a transport manifest (though before a CMS took over, good old Excel macros did the job amazingly well). What they can’t help with is anything outside their operating sphere, anything a practitioner does that is per their SOPs, per their organisation.

Forensic software companies, too, are gearing up and deploying their automation solutions. A lot of these will live in their own ecosystems, but some do play with others. To what degree an automation platform works for an organisation depends on existing tools and procedures, and how much 3rd-party creators open up their software to be automated.

This is not a discussion about the software that plays well with others; this is about the other software.

Automation for the Stubborn

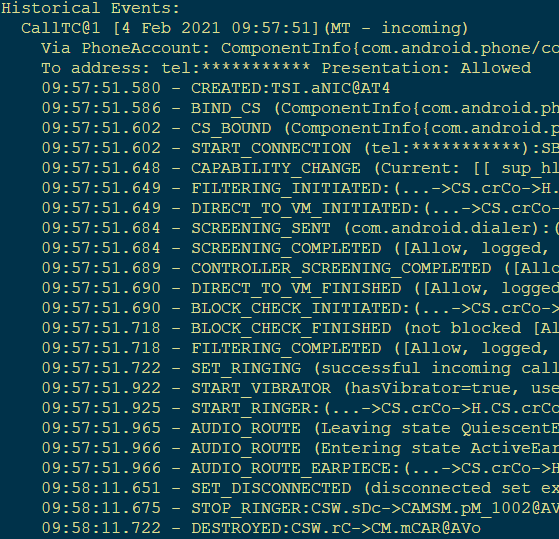

Let’s take a realistic situation as an example. I have an iPhone performing a full filesystem extraction (jailbroken/checkm8/etc.) that’s been running for about 2 hours on, let’s say, a Uniquely Favoured Extraction Doohickey for my PC. Having checked the phone, I know it has about 210GB of data on there, so it’s not going to finish in the 5 minutes before I go home. At first, that seems great – it will keep extracting while I’m not there, meaning no dead time. Except when it finishes in the late hours and sits there telling an empty office that it’s done its job.

When I come back in, I see that it’s finished – great. Now I just have to load it up in some kind of Professional Analysis software, choose any hash sets, processes, etc. that I want and wait a couple of hours for it to load up and finish processing. Reviewing the data, there are a few scripts I want to run and an export or two to make. Now everything is as it should be, I decide to report everything out. And then I wait again. This could potentially roll into day 3.

But what if it didn’t have to wait for me? Surely seeing that the extraction is complete, then making the few clicks and ticks to get it decoded can be done by machine? Yes, they can.

Removing The Human

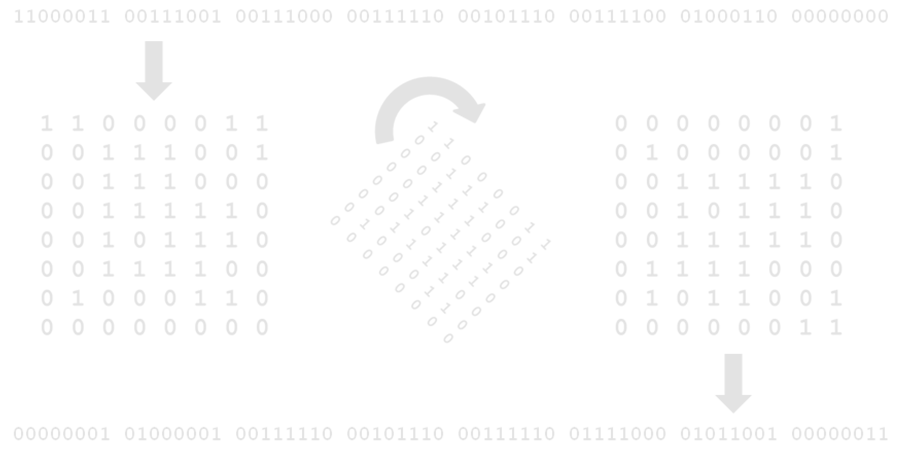

Most programs built for Windows will use default Windows libraries – why create your own window manager, event raiser, buttons, etc. when you can use what Windows provides? And for programs built like this, WindowsUIAutomation has an in. It works for big software, and it works for little Windows Forms applications you make in VS Code. I won’t cover the documentation, but I’ll cover the basics, then how it can be implemented to do what you want.

In WUIA, everything is an Automation Element. Each element has properties, and many have callable functions (Control Patterns). You can Invoke a Button, Toggle a Toggle, and set a ValuePattern for a TextBox. Basically anything a user can do by clicking and typing, WUIA can do. But isn’t this just an old school autoclicker? No. It doesn’t use coordinates, use computer vision of screenshots, POST mouse messages, or any of that – it is part of the .NET Framework that allows this level of accesibility. It does have limitations, but workarounds are available in these fringe cases.

To automate something, you need your own program to run the WUIA aspect. The program you want to interact with becomes the root Automation Element when you create the element from the target process.

C#

AutomationElement rootElement =

AutomationElement.FromHandle(process.MainWindowHandle);This element behaves like every other element you will come across, but because it’s the root, there’s no Invoke or any other methods like that. This is just used to enumerate the child controls contained within/beneath it. This enumeration can be limited to child controls matching user-defined criterea, though these criterea need to be built as Conditions, which I found a little cumbersome in places. For complex conditions, I found Linq extensions to be very useful.

C#

parentElement.FindFirst(TreeScope.Subtree,

new PropertyCondition(AutomationElement.ClassNameProperty, "Edit"))

vs

elementsCollection.OfType<AutomationElement>()

.First(x => x.Current.ClassName == "Edit")These are two ways to achieve the same thing, but the second allows for looking around, e.g. properties of the parent or child control. This is particularly useful when controls have generic or shared names.

Once the desired control is located and method identified, the minimal way to call its functions is like this:

C#

object pattern = null;

element.TryGetCurrentPattern(InvokePattern.Pattern, out pattern);

((InvokePattern)pattern).Invoke();I ended up wrapping this in a function that included null checking and type matching so as not to throw errors all the time.

Now all this is great for simple situations, but unfortunately programs take a little time to do things, and controls pop in and out of existence depending on what’s going on. In addition to methods to find controls and to use the appropriate method with those controls, extra functionality is needed.

Waiting for something to appear can be achieved with a delay timer, checking every 10 seconds or however long to see if there’s a new element matching the Condition. The same can be done with waiting for something to disappear, though WUIA will throw errors of you look for something that doesn’t exist. Finding the count of elements with the matching Condition is the way to go: if count is zero, go about your business.

C#

WaitWhileElementExits(element); // custom wait functionExceptions

Unfortunately, the implementation of some software features, by design or accident, really do not work with WUIA. It is at these time the good ol’ mouse-click simulation has to be relied upon. With WUIA, it’s not a stab in the dark, though, as the framework can provide you with a clickable point on the control and bring it in to focus, so it doesn’t click on the wrong program.

This is certainly the case in a popular Physical Analysis tool when generating reports – one type of custom control used in the software only seems to respond to system-wide mouse-click calls. How an end-user without a mouse would generate a report, I don’t know.

Making It Usable

Hard-coding instructions into a program is not a good idea, and I shouldn’t need to go in to why. That means an automation program would need to be able read a set of instructions. In theory, the automation tool should be able to work with any program, and the instructions could inform the tool which program to load or attach to, and what to do from there.

ACTION#invoke; SELECTBY#Name; VALUE#ExportOkButton;

ACTION#waitwhile; SELECTBY#ClassName; VALUE#ProgressBarWindow;

ACTION#changetarget; SELECTBY#ProcessName; VALUE#paint.exe;

ACTION#invoke; SELECTBY#Name; VALUE#CloseButton;Helpers

Automation on the smaller scale can improve the worklife of DF practitioners too. I call these tools Helpers, because Jeeveses doesn’t roll off the tongue. These can be simple, 4-line scripts, or compiled programs.

To have a usable, searchable storage solution/archive, departments will have some mandated case files organisation or structure. Since it’s in the SOP, creation can be automated. Open your case on your management system, assign yourself to it, create the case folders. A Helper could pull the case reference number (or even case information) from the CMS and know what folders and files you need, and where they need to be. If you need to restrict access on a shared storage location, the Helper could do this too. It saves a minute, probably, but it’s a minute every time you do it, and prevents user-error.

What about the physical production of reports? Not everybody is on a cloud solution yet, and reports will need to be delivered in a usable format. Naming conventions, disk formatting, included documents/documentation – if it’s standard, it can be micro-automated. A Helper could detect when a USB storage device is attached, check its status and specifications, and, after prompting the user, format, name, encrypt, and copy files to the device. (Odd thing: I’ve noticed that the actual formatting of a disk is quicker when running a format command in C# on a ManagementObject.)

C#

volume.InvokeMethod(

observer,

"Format",

new object[] { "NTFS",

true /*quick format*/,

4096 /*cluser size*/,

newName,

false /*compression*/}

);Paginated HTML reports (as some software still produces) can be less than ideal. Helpers can change page-based item indices to global indices (i.e. “Item 1” does not appear on each page, but is continues over the pages), resize or replace images, remove or add table columns, or format to a corporate/organisational theme.

The Dream Is True

Home-grown automation won’t replace the human aspect of DF, but it can replace the machine aspect of the job, the tasks that require no specialist skill or knowledge, just time. What could work look like for this practitioner?

They would open the case on their CMS and familiarise themselves with the circumstances and requirements. They’d open a Helper that would see the case they have open and ask if they want case folders creating for them. It pulls the exhibit references and types from the CMS and makes the folders. They open their extraction software, set the destination to their new folder, and start the extraction. Then, they point their WUIA tool at the extraction software and set their parameters. Barring any issues, they free to engage with something else.

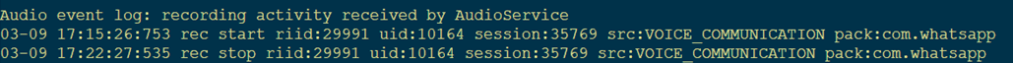

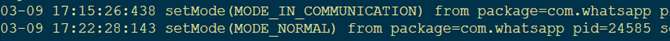

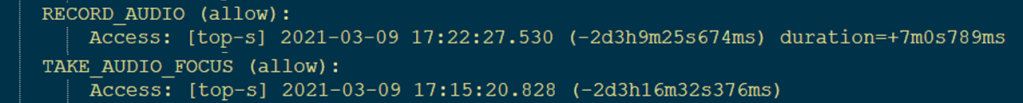

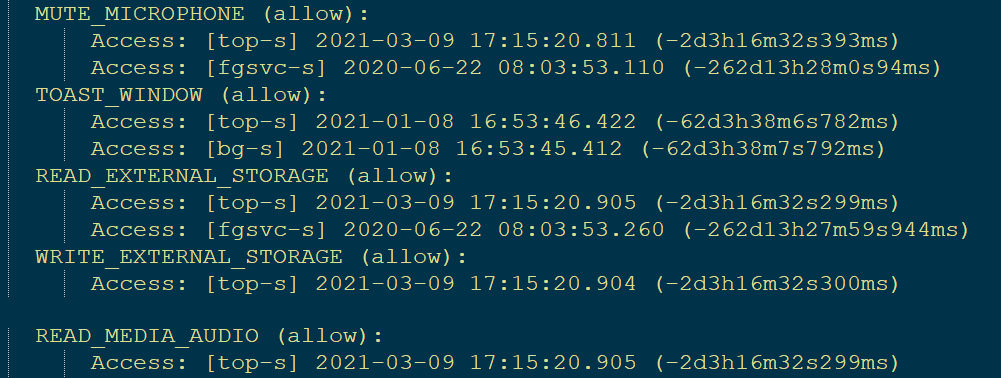

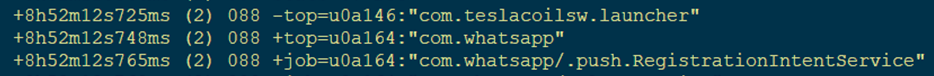

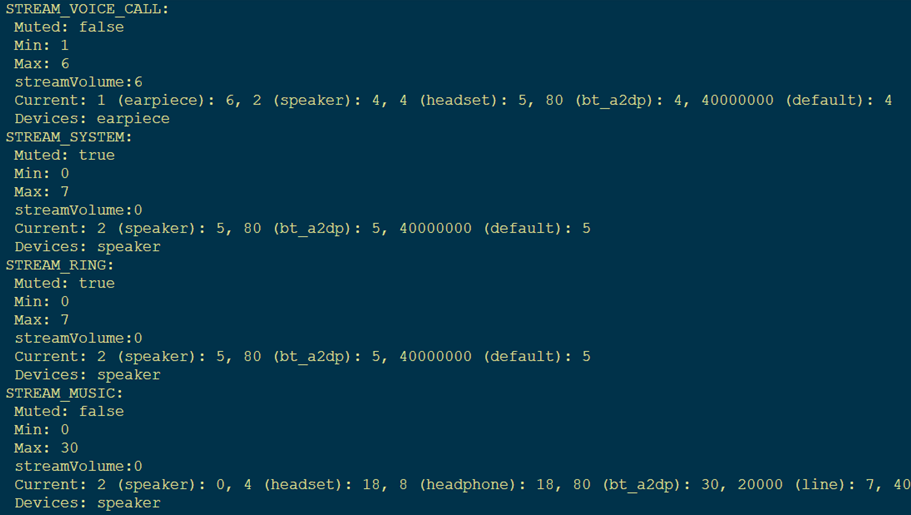

While working on something else, or on a call, other in anyway otherwise engaged, the extraction finishes. The automation tool sees this and loads it into the analysis software. It’s been told to run 3 scripts, 2 watchlists, a hash set, and export all videos, so it follows the instructions and does this. WhatsApp content has decoded, which is the other artefact the case is looking for, so the tool pilots the analysis software to create a report. The practitioner returns and finds their videos and report.

After reviewing the data they decide no more analysis is needed and the generated report is appropriate, so they go to produce a USB. They plug a new one in, and a Helper sees an unprotected, empty drive. It asks the practitioner if it should be formatted and encrypted using the case details from the case open in the CMS. It does this and asks the practitioner if it should generate a template continuity statement.

All in all, the practitioner has done no less skilled work than normal, applied the same standards and quality, but has done less peripheral work manually, and has eliminated an amount of dead time from the process.

The Wrap-Up

Automation cannot be left to the big companies. What they are doing is fantastic, but not specific to anybody’s practices, and only within their sphere of interest – there’s so much more that we can have tools for. Let’s make them.

The code I have written is theoritcally generally applicable, but was written to target a particular software suite. The code and tools are not currently available to the general public.